It was a moonless night and we had been driving in the dark for some minutes, following the unclear directions they gave us at the gate, so it took a while to find the cabin. The first thing we saw when we switched on the light was this sign above the kitchen sink.

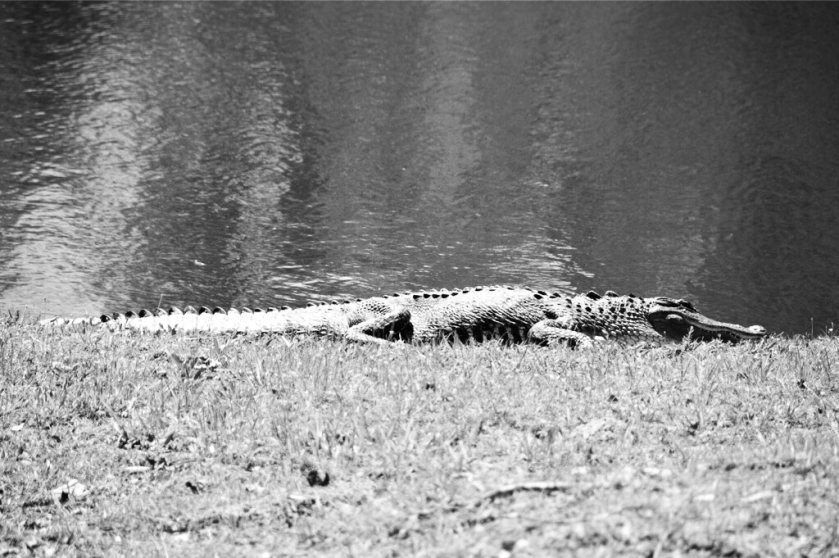

I thought it was one of those jokey kitchen signs people put up, like: “We only serve the finest wines. Did you bring any?” But the next morning we realized the cabin sits on a narrow strip of land between two ponds in which alligators do, in fact, float like half-submerged logs, their dead-seeming eyes peering just above the surface. They’re everywhere on the property, like squirrels are back home, although with less frantic energy. Driving around, we saw several that had dragged themselves onto the bank to warm in the sun, the largest of them a seven-foot monster. Folks say gators can run surprisingly fast, when they have a mind to.

Advice from my sister-in-law, when she phoned from Montreal: If an alligator gives chase while you’re out running, immediately start zigzagging, as alligators can’t easily change direction.

Lowcountry

We’re staying in a gated community in South Carolina’s Lowcountry, near the town of Bluffton. The place is so vast — 20,000 acres, encompassing the lands of 21 pre-Civil War plantations — that they recently hosted a marathon entirely on site.

They call it low country because it’s just about at sea level, give or take a couple of feet, which explains the wetlands, the alligators and the many miles of riverfront at your doorstep. We’ve arrived just in time to witness great masses of pink and fuchsia-coloured azaleas in bloom, a visual tonic after months of colour-starved Canada. The live oaks are just coming into leaf, too, and the roads are like dripping tunnels, as the oak branches meet overhead and trail long wreaths of Spanish moss. Strangely ghoulish at dusk, the scene becomes spectral in the early morning light, the limbs like crooked bones clothed in shimmering green ectoplasm.

It’s so picturesque as to seem like a parody of of the South. But it’s real and the residents appreciate what they have and want to share it, which is why our gracious hosts provided us with a waterfront cabin, or “bunkie,” as they call it here.

On the first day, we made sure to visit the new community centre, comprising art studios, conference rooms, upscale restaurants, pools, bowling alleys and other amenities.

It’s quite easy to find: turn right at the first corner, then go past the equestrian centre (173 acres) and the shooting club (40 acres).

Y’all come back, now. Hear?

We were here two years ago, and enjoyed the same southern hospitality. Each time, we learn a little bit more.

Like many places in the South, the adjacent town, Bluffton, was put to the torch during the Civil War, although eight homes did survive, most of which are now restored and occupied by professionals, as the gleaming Volvos and Acuras in the driveways suggest.

The sea-facing bluffs, for which the town is named, catch the distant Atlantic breezes and make Bluffton comparatively cooler and less plagued by mosquitos. In antebellum days, it was a refuge from malaria during the blazing summer months. Plantation owners packed off their families here for their holidays, so the town grew fairly prosperous before the war, but entered a long decline immediately after.

The last time we were here, we arrived directly from Savannah (we’re finishing up in Savannah this time), so I was struck by official and unofficial attitudes toward the South’s troubled past. Our Savannah tour guides, for example, maintained a neutral tone about the grand homes we toured: about the families that lived there, their rising and falling fortunes, and where they fit into the larger society. For the most part our guides stuck to the script.

But the moment we entered the slaves’ quarters, the guides lost several degrees of coolness. They made plain where they and the local historical society stand: slavery remains an unregenerate abomination, without palliating conditions, explanations or context.

I remember, particularly, a child’s room with an enormous high-canopied bed topped with bolsters and feather pillows. At its foot was a large chest for toys. On the floor beside the bed was a thin mat where the playmate curled up.

Back in Bluffton

Several days later, I wandered through Bluffton to admire the old homes. Among them is the Heyward House, built by slaves in 1841 for their white masters, and now run by the local historical society. For a few dollars you’re permitted to walk through the cramped rooms and feel like an interloper, peering at the household belongings of wood, leather and iron, ivory, bone and glass.

Out back, more belongings: a one-room shed and a patch of dirt indicates the slave quarters.

I was the only visitor, and the young woman who greeted me, a volunteer, was clearly proud of her town and its past. I don’t know what kind of training she’d had, and whether she was expected to follow any official line. But I did ask some questions, and when she saw that I was genuinely interested in the town’s history, and clearly not from these parts, she informed me that, contrary to what I may have heard or read, the Civil War was primarily a clash of civilizations — a largely rural, agrarian and communitarian society (the South) coming up against a mercantilist, industrial and urban one (the North).

Somehow, in her explanation, slavery got misplaced. Never even came up. Yes, there were slaves. Of course there were! Why, their quarters are right there in back, if you care to look. But that’s hardly the whole story…

I think of the alligators and their inability to change direction. But I remain hopeful.