We had not visited Paris in years, and had forgotten how it is positively bursting with culture. Out for a walk, you’re elbowing through crowds of Rodins, tripping over mislaid Canovas and Fragonards.

Continue reading “Pissing at the Louvre”

We had not visited Paris in years, and had forgotten how it is positively bursting with culture. Out for a walk, you’re elbowing through crowds of Rodins, tripping over mislaid Canovas and Fragonards.

Continue reading “Pissing at the Louvre”

As I write this, I am sitting at a small plastic table outside our room at Shea’s Riverside Inn and Motel in Essex, Massachusetts.

Our room, the Fredonia (#14), is flanked by the Caviare (#12) and the Eugenia J. (#15). Eugenia is the belle of the motel, as she offers a panoramic view of the Essex River estuary, whose waters empty into the Atlantic and, throughout the spring and summer months, supply tourists with great clouds of small biting insects.

Apart from these facts, Essex County is the birthplace of the comedian Bo Burnham, as well as the birthplace of the fried clam.

But all that is recent history. For in the 19th century and into the 20th, Essex was a shipbuilding powerhouse. It produced more two-masted fishing schooners than any other place in the world. Of the 4,000 schooners built in Essex — an astounding number — fewer than ten survive.

At the Cape Ann Museum

If you visit the Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester, you’ll find an entire wing dedicated to the painter Fitz Henry Lane (1804–1865). His many views of Gloucester harbour are sublime, luminous; as are his paintings of wooden schooners, which were mostly built in nearby Essex. Shipowners commissioned Lane to paint their ships, the way people today want portraits of their dogs and bungalows. You can see why Lane was kept busy. His paintings are impressively detailed and, as the plaques point out, easily withstand close scrutiny by the most demanding maritime historians. There isn’t a knot or plank out of place.

But after a while (these are not my dogs, my bungalows), the paintings all become rather the same thing: handsomely painted, closely observed wooden boats. The eye wanders, attention flags. You may as well be looking at paintings of haystacks and water lilies. And yet, Lane’s paintings of ships endure, even as the ships themselves moulder at the bottom of the ocean.

I’m reminded of a visit to Prague Castle many years ago, roaming through a maze of stone galleries filled with seemingly identical paintings of the Madonna and Child. One echoing room after another, and everywhere the insipid smiles, everywhere the pasty flesh, the pervasive and suffocating sense of rapture and doom — for you know how this story ends. In shipwreck and, ultimately, in exaltation and boredom.

* * *

Somewhere in my basement is a box with a photographic portrait of six-year-old me. The photo is printed on textured, heavy paper, in shades of warm grey.

A photographer has been engaged, Greek of course. My mother has dressed me in a striped short-sleeve shirt and cuffed shorts. She hovers. The photographer places me on a coffee table, sideways, tells me to bend one knee. He tells me to smile, tilt my head. Hand under chin, now. Thoughtful. That’s it, now hold it.

Growing up, this photo was inescapable. For a long stretch, it was in an easel-backed frame and sat on a side table in the living room, a constant smiling rebuke. Always and everywhere, you are nothing more than this.

Fitz Henry Lane at the resurrection

Born Nathaniel Roger Lane in Gloucester, the painter apprenticed to a lithographer in Boston before returning home to launch his career as a maritime painter. What else we know about him: He was lame from an early age and went about on crutches. He may have been a Spiritualist. He never married. At age 26, he successfully petitioned the Massachusetts General Court to change his given names from Nathaniel Roger to Fitz Henry. No one knows why. This is one of several mysteries that attach to the artist. Here is another:

The house Fitz Henry Lane built, from Cape Ann granite, is today owned by the City of Gloucester. Handsome, plain and freshly cleaned, it stands on a hill at the waterfront and commands a fine view of Gloucester Bay. But for a long time after Lane’s death in 1865, the painter was forgotten and his many portraits of ships collected dust in grand houses throughout Boston and Cape Ann. Meanwhile the Lane House sat alone on its hill, neglected. It passed from one owner to the next.

Among these owners was the Polisson Family. Wandering through the Cape Ann Museum, I come across a black and white photo of the Polissons, in front of their new home. A date is scratched into the lower-right corner: April 6, 1914. The date is in Greek.

Five Polisson children sit cross-legged on a kourelou village rug in the foreground. Directly behind are two seated bouzouki players, in suits. Between them is a third man in a suit, possibly the singer. Other family members in white shirts and dresses stand at the back and form a kind of frieze or chorus. On the left is a moustached man with a cigar clamped in his mouth. He holds a tray of glass tumblers filled with wine. A man to his right, in a flat cap and tie, holds a roasted lamb on a long wooden skewer. The Easter feast is about to begin.

A quick picture, then, before we eat. That’s it. Hold it, now.

* * *

Jesus in Prague comes to mind. How the wheel of time turns, how things come round, with the seasons and the generations, but always with small surprises, with fresh signs of death and resurrection, with evidence of the sublime and ridiculous.

I’m sitting in Cafe Sicilia, in Gloucester, Massachusetts, listening to a couple of beefy men engaged in grave, whispered conversation. They’re tanned and wearing work clothes and speaking in what sounds to me like an Italian dialect. A lady offers them a seat on her bench, since they’re standing. But they politely decline, down their espressos and leave. In a corner of the café, a family of five sit in front of their untouched cannellonis. They stare at their phones.

When you enter Cafe Sicilia, the first thing you see is a five-foot square piece of AstroTurf glued to one wall. The AstroTurf is decorated with red neon letters that say Ciao!

The other thing you’ll notice is a three-foot-high painted statue of the Virgin and Baby Jesus. They stand on a high shelf above the counter: Crowned, solemn, making gestures. To the right and just behind the Virgin’s skirts is St. Joseph. He’s about a third smaller than the wife, but doesn’t seem to mind. Immediately to the left of the Virgin and Child, like a shimmering crowd of worshippers, stand a dozen bottles of bright green dishwashing liquid. These are for sale.

Rough business

On our first visits to Gloucester, some years ago, the waterfront was rougher. People had warned me, made jokes about it. But there’s nothing like the sight of a drunken sailor, normally part of a punchline, to cure you of the notion that there’s anything funny about a drunken sailor. You see less of that now, maybe because of tourism and gentrification.

Tourists and their money are welcome in Gloucester, but the real business is still out there, on the water. It’s a rough business. You can tell as soon as you drive in. The roads are clogged with massive tractor trailers, circling the warehouses or parked with their engines running, waiting to be loaded with fish. There used to be more fish. But in the crowded harbour, big trawlers still tie up at Cape Ice to fill their holds (with blocks, cubes, crushed ice or shaved) before heading out to sea. Meanwhile the surrounding yards — filled with rusting iron hulks and decaying wooden boats — function like ICUS. Large men with tools clamber over the stricken vessels all day, fighting to stem the decay.

Gloucester was first settled by Europeans 400 years ago, making it one of the oldest ports in the United States. In the 19th century, these waters were still seething with so many fish there simply weren’t enough skilled hands to get them onto boats and to market. So the Irish came for the steady work, followed by the Portuguese (mostly Azoreans) and Italians (mostly Sicilian). Canadians arrived, too, by the boatload. By the end of the century about half the workforce was Canadian-born, largely from Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.

These immigrants prospered, bought and manned their own boats, started families, built churches and, for those lucky enough to not die at sea, filled cemeteries.

* * *

During our three days in Gloucester, I’ve lingered at Cafe Sicilia three times. The espresso here isn’t the best in town. And, to tell the truth, the cookies and pastries aren’t all that good either. But why would I take my coffee anywhere else?

I haven’t posted a short story about Park Extension for a long time. For those of you who don’t know, or need reminding (that’s how long it’s been since I posted a bit of fiction), Park Extension is a working-class neighbourhood in Montreal that has, for many generations, been a home for new immigrants. In the years I spent there as a child and adolescent, Greeks probably made up the biggest ethnic group. Most of the Greeks have moved on, although their churches remain.

I hope you like the story.

It’s titled Clothes Make the Man.

In the morning, while the Germans, Americans and Brits sleep off last night’s dinner, the ladies are out among the gardens. Over faded dresses and threadbare slacks they wear reflective safety vests, they carry brooms and rakes. As they chat about last night’s TV show, the state of their kids and husbands, they clear the paths and flower beds of twigs and fallen leaves, and by mid-morning they’re gone.

During these same morning hours, I wander the formal gardens facing our hotel in Kérkyra (“Corfu,” to non-Greeks) to snap pictures of its many statues. Uniformed and besuited Worthies, carved in marble, are scattered through the winding paths. Famous generals and prime ministers, scholars and bureaucrats, all of them men, all of them briefly astride History.

Kerkyra is parked just off the coast of Greece, in the Adriatic, which makes it a geopolitical prize. And so, for centuries the Great Powers each took their turn. Venice installed its Worthies and ruled for centuries. The French had two goes at Kerkyra, the second time led by the megalomaniac Napoleon. After they ousted Napoleon, the Brits stayed on for a bit. Then they decided Kerkyra wasn’t worth the trouble and, following Greek Independence, “gave it back.”

But it was a 19th century view of independence. Out for a run one day, I pass the Mon Repos Palace where Prince Phillip (William and Harry’s grandad), of wholly German stock, was born in 1921.

* * *

A few days before our arrival in Kérkyra, we were staying in the town of Kalambáka, beneath the monk-haunted mountains of Meteora. One evening, as we were walking toward the agora to scope out a taverna for dinner, a Dutch woman turned to me and confided that she always felt nervous speaking with Greeks. She would eventually have to reveal her Dutch background, and might be blamed for the punishing austerity measures Greeks endured after the global financial crisis of 2008. Tens of thousands of Greeks were left homeless, families went hungry, suicide rates spiked. As society went into freefall, the public safety nets vanished.

The Dutch woman, a retired chief executive of a global consultancy, said it had all been very unfair. I, too, remember the news stories, and the unspoken judgments: Lazy, feckless, corrupt, irresponsible. They had it coming.

In Canada, among Greek friends, we looked at each other guiltily. Wasn’t there some truth to the charges? We traded our own stories of maddening bureaucracy, reckless spending and tax avoidance.

“But Germany was mostly behind all those austerity measures, wasn’t it?” I asked the Dutch woman.

“Yes, but a Dutch Eurogroup president carried them out,” she responded. “Greeks would remember this.”

I reassured her, without any real knowledge, that it was water under the bridge. Greeks are hospitable people, so how could anyone possibly blame her? We had all moved on.

It was not a good answer, but it was the best I could do. We found a taverna and our group ordered an excellent dinner, with a couple of litres of local wine. It was a memorable evening with much laughter.

A burden on society

Objectively speaking, Uncle Pavlo, who lived with his family a few blocks from our apartment in Park Extension, was a failure. After arriving in Canada, he started several businesses, but they all went bust. As for steady work, he never managed to hold a job for more than a year or two, often just a few months. He’d work long enough to qualify for government benefits, then quit or arrange to get fired. He did that for years, supplementing his meagre UI cheques with the odd part-time job, always for cash. He bought a car, but then lost his license for driving while drunk.

By my high school years, Uncle Pavlo had settled into a tolerable routine. When the UI forms arrived each month, he’d find me at the back of my father’s small store. I was usually at the meat counter, eating a sandwich of warm Greek bread, mortadella and cheese. And beside me, always, a sheet of butcher paper with a tomato cut into wedges and a handful of olives.

“Sorry to interrupt, Bárba Spyro,” he’d say, handing me a pen and his UI forms.

Between bites, I’d tick off the boxes. Yes, he had been available to work. Yes, he had looked for a job. No, he had not succeeded in finding one. Sign here. Date there. I suggested that his kids, both of them about my age, could just as easily fill out the forms. Nope. The cheques kept coming, so why tempt fate?

Meanwhile his kids needed winter boots and school supplies. Money was always short for rent and utilities, for bus tickets to get my aunt to her factory job. There were never vacations.

I also remember several other things about Uncle Pavlo. For instance, he was a good cook and taught me several classic dishes, including tas kebab. When he had a few dollars, he joined his cronies at various Greek dives in Montreal, where he was a legendary drinking companion. He could be hysterically funny. When Uncle Pavlo was “on,” with a beer parked on the table in front of him, he would hold a room for hours. On Saturdays he played the fiddle in a Greek dance band. Sometimes I watched him practice, his thick, nicotine-stained fingers confounding all expectation, as they raced up and down the fingerboard to conjure a maiden eagerly skipping along a mountain path and into the arms of her lover.

Until the day he died, Uncle Pavlo called me “Bárba Spyro,” a common endearment for an elderly gentleman. He began calling me “Bárba Spyro” when I was in grade school. I must have been a serious kid.

* * *

Later in the day, roaming the narrow lanes of Kerkyra, we come across a yiayiá with her broom. It’s such a common sight throughout Greece that, after a time you scarcely notice them. Ancient women eternally sweeping their front steps as a cat sleeps under a pot of basil.

The Ant and the Grasshopper

No one knows what Aesop looked like, but in sculptures he is always ugly and troll-like. According to ancient accounts, Aesop was a former slave. Some place his death in Delphi, maybe in 6th century BCE. But the history is murky. We really don’t know much about him. Even Aesop’s existence is in dispute. The first and greatest fabulist may have been a fiction himself.

One of Aesop’s best-known fables, “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” has been endlessly retold, reinterpreted and illustrated to suit every age. You know the story.

Winter arrives, with howling vengeance, and Grasshopper makes his way to Ant’s snug little cottage. Hungry, cold and bedraggled, seeking shelter, Grasshopper bangs on the door. The door opens a crack, then swings wide to reveal Ant, who is wearing bunny slippers, a green woolen housecoat lined with thin-striped red satin, and a warm nightcap. Behind him, a fire blazes on an iron grate. Ant surveys the shivering Grasshopper, grimaces at the fat drop of snot trembling at the tip of a red nose. Ant clucks his tongue.

“Well, will you look at that. While I slaved all summer long, while I prudently stored up food and provisions to tide my family through the winter months, you, Grasshopper, you sat lolling on a sunny rock and sawing at your fiddle all day. Without a care in the world, eh? Now, here is the day of reckoning at last.”

And with that, Ant slams the door in Grasshopper’s face.

The dude ranch has a couple of hundred horses, four of them mustangs and all of them geldings. With their testicles removed, the horses are gentler and less skittish. That way city folk are less likely to break their collarbones and litigate. Everyone is happy.

As for wilder terrestrial varmints, I’ve now seen several, even though it’s winter and many of the most interesting ones are under rocks, fast asleep.

While out running one day, a coyote crossed the road a few metres ahead of me. I later saw a small lizard sunning itself on a rock. And then a scrap of dark fur scrambled across my path as I was hiking in Saguaro National Park.

Javelinas at the cookout

At the Cowboy Cookout one evening, the cowboy music conjured several javelinas from the surrounding darkness. I suppose they had been waiting for the city dudes to be seated with their grub, before materializing to lurk beneath the serving tables, snuffling for scraps of cornbread, shreds of pulled pork and brisket. A ranch employee came over and shooed them away, but the javelinas were back seconds later, nose to the dirt, eyes alert.

They’re about one-third the size of a wild boar but narrow on the x-axis. Two-dimensional wraiths, paper silhouettes sliding soundlessly between a forest of table legs. If a javelina turns to stare at you with its tiny black eyes, it’s reduced to a bold vertical pen stroke. And when it moves, it’s in an odd start-and-stop manner. A few quick steps, stop. Some more quick steps, stop. Like a housefly.

Alas I saw no Gila monsters on my hikes, even though I was smack dab in the middle of Gila monster country. These are the biggest and heaviest lizards in the U.S. They’re also venomous, as their orange and black mottling suggests. If you were to meet one, it would be like running into a fat-bellied salami, but with legs. And don’t you fret about that venom part, a pamphlet reassured me. Gila monsters are exceedingly slow moving. But the pamphlet also noted that Gila monsters dine mostly on birds, rabbits and mice. So I’ll take the “slow-moving” part with a grain of salt. I know for a fact that I can’t catch a bird with my teeth.

The animal within

When you’re the son of a butcher man, as I am, you’re raised to have a casually utilitarian view of our fellow creatures. You eat ‘em, nose to tail. Nothing wasted.

But as an urban elite living in these times, I don’t know what to think or feel about animals anymore. A noisy group is currently lobbying Ottawa for a ban on the export of horses to Japan, where horse flesh is delicious. A friend emailed to ask if I’ve eaten snake in Arizona — if that’s even a thing. Meanwhile the twice-weekly Cowboy Cookout, at the dude ranch, is a grand and jangling festival of meat and more meat. There’s always a fish option, which I reckon to be a recent innovation. But let’s not kid ourselves. That’s meat, too.

* * *

I must have been ten or twelve years old, when I first took the long drive with my father to a slaughterhouse. It was summer, school was out, and there was only so much you could do to amuse a young boy, I suppose. Might as well show him the business. I made several more trips over the next few summers, and saw things I probably should never have seen. The images and scenes have stayed with me ever since, and I’ve never managed to put them into words. Nor will I do that now.

Of course, farming people, the folks who live with and raise animals, entertain few illusions about what it’s all about. I have fond memories of my loving aunt in Greece. A happy quivering little goat perched in an olive tree. Later, God bless us, a sumptuous Sunday roast prepared in a traditional tapsí, surrounded with potatoes and fragrant with oregano and lemon.

My father didn’t think twice about taking me to the abattoir. For this had been his childhood, too. Maybe less mechanized, a little more shrink-wrapped, but fundamentally the same. The facts of life and death laid bare.

But what my father failed to grasp is that we live in a more complicated time and place. So when I entered the house of horrors, it was like taking a twelve-year-old boy into a strip club.

The kid has never seen ladies without their clothes on. So you buy the kid a beer and a lap dance. Order up shots.

“Hey, have some more peanuts, kid.”

You push the kid onstage for his first slow dance. He’s sandwiched real hard between Luscious Lola and Desiree, who are grinding their hips against the kid. The kid doesn’t know what to think. A number of other naked ladies are also present, writhing on poles. All around, men are making loud suggestions.

You take the kid to the strip club again. After a time, it becomes easier for the kid and you. Then you expect the kid to grow up and have a regular relationship with women.

That sums up me and meat.

Also, peanuts will never again taste the same.

I’ve gone for a few runs at the Arizona dude ranch, where we’re staying. But frankly I’d rather hike in Saguaro National Park right next door. Because, after all, when will I ever get a chance to hike here again?

The desert climate makes it tough to run in any case, especially if you’re not acclimatized. I can’t carry enough water to go very far, and there’s no refuge from the sun, wind and my own bad judgment.

Here’s what I’ve learned. If you visit these here parts and plan to run, do not run within three hours of a roast beef Sunday brunch. A more prudent length of time to wait is three days.

The beef, mashed potatoes and palate-scouring horseradish were excellent. And they remained excellent for hours. Because I limped for eleven kilometres that afternoon, and I could taste them every damn inch of the way.

* * *

We were driving to a restaurant in Tucson, one night, when the subject of cowboys came up. I wondered aloud about Europeans’ odd fascination with the frontier mythology: Italian spaghetti westerns come to mind, where Clint Eastwood made his career. But also Germans’ near-obsession with cowboys and especially Indians. (Theme parks devoted to Indians are still in business. Once a year, devotees wear feathers, sleep in teepees.) There’s a writer of cowboy adventure books from the 1920s, I said to my audience in the van — “Surname of May, I think” — that had a huge influence. Many of the themes he wrote about dovetailed with Germans’ growing appetite for “authentic folk” and nature, for the cult of the body, violence and race, which eventually led to the rise of fascism (hello “Yellowstone”). But after so many years I couldn’t quite dredge up the German writer’s full name.

Also, I could hear my pompous self, lecturing and blundering in near-total ignorance, into touchy territory. So I did everyone a big favour and shut up.

Magic Tom in the Adirondacks

In Park Extension, where I mostly grew up, we played cowboys and Indians all the time. For afternoon TV, we had muscular John Ford westerns, or Roy Rogers cheesecake. In summer, a local TV entertainer for kids, Magic Tom, took his show on location to a dude ranch in Upstate New York. Frontier Town featured bloodthirsty Indians, daily shootouts at four o’clock sharp, and fistfights that spilled out of the local saloon. I dreamed of going, but for a kid from Park Ex, this was next-to impossible.

Our book club recently read Lonesome Dove, by Larry McMurtry, which is a masterpiece among cowboy books. (Or so I’ve heard, since I’ve long since moved on from all that.) You need to suspend plenty of disbelief to read Lonesome Dove, and also judgment. You need to look past the book’s casual assumptions about Blacks, Mexicans, Indians and women (in alphabetical order). Not to mention its views on colonialism and justice, on society and civilization, on nature and wildlife. Lonesome Dove is set in the 1870s, but it more clearly reflects the views of the 1980s, when McMurtry wrote it.

And yet, if the views in this book seem retrograde fifty years after it was written, how much more alien seem the views held by ordinary folk (by that I mean white males) 150 years ago.

So how to enjoy a book that would likely be offensive and even unreadable for most African-Americans, Mexican-Americans, feminists and Indigenous People? You enjoy it by being a white male of a certain age. By having played Cowboys and Indians in more innocent (i.e. ignorant) times.

It’s hard not to like Lonesome Dove. It’s so damn charming, so cunningly written and packed with mythical figures and action. I read McMurtry’s essays for years (he died in 2021), and loved his dependably funny and informal Texas drawl on the page. But beneath it all he was a highly educated, deeply intellectual dude. He knew what he was doing but, like all of us, he was a prisoner of his time and generation.

* * *

After we returned from dinner, I googled German writer of pulp westerns. His first name was Karl, and I was wrong about when he wrote. Karl May was born in 1842, so he was a cultural force long before the 1920s. He began his career as a con artist and wound up serving time in prison. Then, without ever having set foot in America, he began writing westerns. And he was so good at spinning yarns that his books have since sold 200 million copies. He’s the best-selling German writer of all time.

Generations of German kids, especially boys, devoured his books. Young Adolf was a huge fan. Later, when Adolf became more famous, he recommended the books to his generals. You can see how frontier stories would set Adolf’s boyhood imagination on fire, and how this could lead to further musings about a world unfettered by laws and civilization, where scores were settled with guns, and the stakes and struggles were simple and stark.

But, in fairness to May, you can find whatever you want in any book. Karl May was sympathetic to the Indians, admired Jews, and was a committed pacifist.

How does one enjoy books like Lonesome Dove or Huckleberry Finn? What about a kids’ book about a gay couple taking their toddler to her first opera, or a Dolly Parton lookalike contest? How do you keep these books from being locked in a basement — or worse, burned?

These here subjects are complicated. Too complicated for a city feller out for a ride on his blog — a feller whose eye even now is wandering to the word count at the corner of his screen. Time to move on out.

Jimmy, who is a horse wrangler at the dude ranch we’re headed to, meets us at the Tucson airport and helps us load our bags into the ranch’s white van. On the drive, Jimmy explains how he arrived at wrangling by way of working at a dive shop in Baja, Mexico. On his very first dive, Jimmy came face to face with a hammerhead shark. Also, there was an ex-wife and her family back in Denver, where he grew up. They owned the dive shop. There may have been another wife. At some point things got complicated.

It’s after eleven at night and we’re a little woozy from a long day of travel.

Jimmy takes a detour to show us the massive “boneyard,” where some 4,000 decommissioned military aircraft are parked. It’s the biggest in the world. I peer into the dark but don’t see a thing. Jimmy admits that he sometimes misses diving. If you’re bitten by a rattlesnake, he cautions, do not do like in the movies. Do not open the wound and suck out the venom. That might be the last thing you do. I’m still looking for the 4,000 aircraft. Any one of these aircraft, which I can’t see, can be operational within seventy-two hours, he says. Standing orders from Washington, just in case. On a typical day at the ranch, Jimmy collects a dozen or so rattlers. He uses one of those gizmos grocers once used to fetch down your box of corn flakes from the top shelf. He drops the rattlers into a barrel and drives them out for “relocation.” No sense killing ‘em. It’s winter, though, so the rattlers are asleep.

“Hibernating?” I offer.

Jimmy gives me a sideways look.

Big ole saguaros

Maybe Jimmy is right about the rattlers. On my two hikes, I have yet to see a terrestrial varmint, except for the occasional road runner. There are coyotes and bobcats, apparently, as well as javelinas (pronounced with an aspirated “J,” like “Javier”), small pig-like scurrying creatures with sharp tusks. Jimmy warned us that they can be mean tempered and territorial, in the usual way of snouted things.

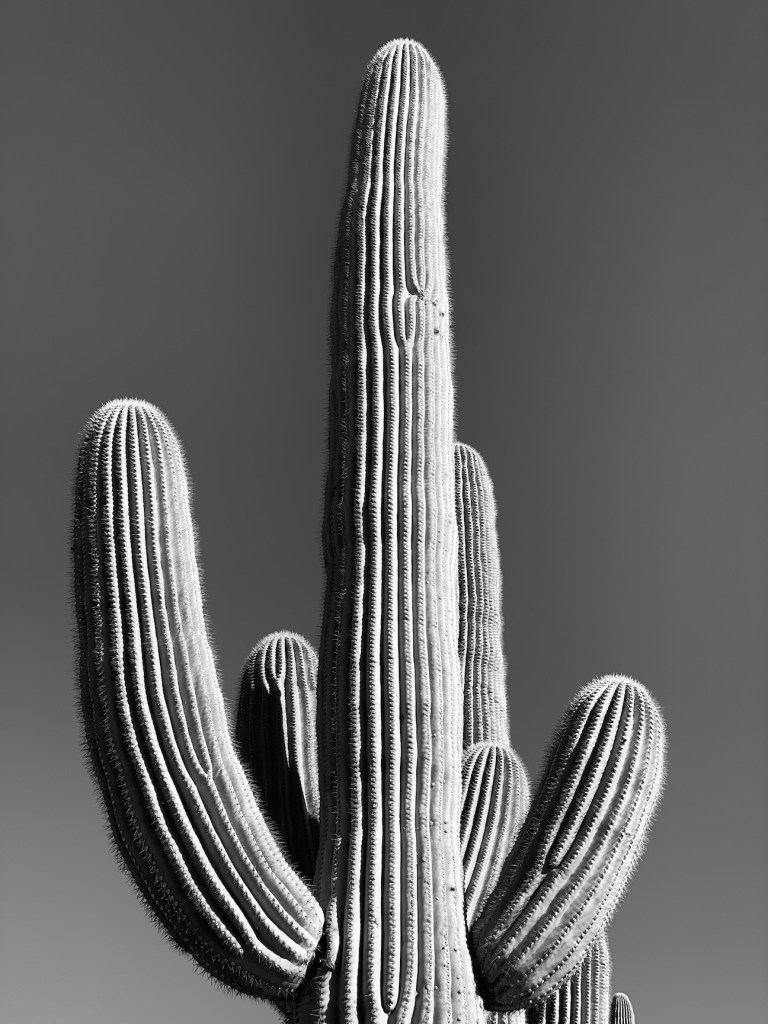

Our dude ranch sits beside Saguaro National Park, named for the iconic cactus you can’t help but associate with cowboy movies and logos for rolling papers. Saguaros, which cover the ranch grounds and surrounding landscape, typically live for hundreds of years and grow more than forty feet in height, but ever so slowly. A saguaro no bigger than my thumb is ten years old.

But with great age comes dignity. Among the twisted mesquite, the low, clinging vegetation and rock-strewn hills, these towering cactuses possess a formal, dignified verticality. Like giant butlers: straight-backed, waiting patiently to be summoned. At their feet, a cluster of prickly pear disturbs their dignity. Round-eared, snot-nosed, like green Mouseketeers.

Aging with George

I have time on the ranch to consider the ancient saguaros, which will long outlive us. The desert itself, with its thousands of decommissioned aircraft parked somewhere out there, seems ageless, unchanging. But I already know better.

On our second day at the ranch, an elderly Mexican gentleman in a black hat, cowboy boots and a neat goatee detaches himself from his family to greet us. His name is George, and in the way of the very old and very young, he’s eager to talk about his great good luck: it’s his birthday! Oh, yes, his son has paid for a special weekend celebration with the family at this dude ranch. There will be a horseback ride, with a pancake breakfast on the trail, then prime roast for Sunday brunch. We congratulate and wish him a happy birthday.

George is a sweet old man: grateful, excited, eager to experience new things. But age does tricky things with some men, especially men. Too many become bitter, prickly; mourning their mounting losses and regrets. Even with the best of intentions, loving sons and daughters listen less, ask fewer questions, make less room in their busy lives.

The firelight dims, the sound of drums recedes.

My own father, who came to Canada nearly penniless, who had a dishwashing job lined up for the morning after he arrived in Montreal, who built and lost three businesses, who never learned English or French, who took his young son to the bank to arrange for loans, who kept faith with his youthful politics, who was respected by all for his judgment and sense of justice, and who always sided with the poor, the powerless, the already-beaten, in old age grumbled about the new immigrants, who had it so easy, who were showered with government money and benefits, and who were just too lazy to work.

Then I stop and consider all he’s been through, the wrenching displacement, the impenetrable languages and customs, the years battling illness and disillusionment, and the bitter old man is little ol’ me.

* * *

George points to his son, who is now glancing over, politely smiling but also wondering how to disengage his dad from these nice strangers so the birthday weekend can resume.

But George is clearly bursting with pride, for his handsome son and his beautiful family, for what a long life has brought him — this special weekend in his honour, this chance to share meals with his loved ones, a horseback ride, adventures. Life is full, and he wears old age like a crown.

At breakfast one morning, a member of our group — I’ll call him Bill — offered to lead us to the ancient monasteries and caves of Meteora, high above the town of Kalambáka. Bill had hiked the area on previous trips and knew his way around. Before we begin our climb, he suggested, our first stop should be Kalambáka’s own Byzantine church.

The day was bright and sunny as we entered the churchyard, and the instant she saw us, a sweet old yiayiá rose from her taverna chair by the church entrance to greet us. Her shy smile instantly brightened when I spoke to her in Greek, and a flood of information followed.

Dedicated to the Dormition of the Virgin Mary, the church sits in the oldest part of town, well away from the busy squares and traffic. As it is hidden in the shadows of Meteora’s cliffs, both literally and figuratively, most tourists who flock to the monasteries bypass this church altogether. They don’t realize that it was built hundreds of years before the monks and hermits arrived. That a temple of Apollo stood on the very same spot, making it a site of worship for thousands of years.

We stepped inside. The interior was busy and cluttered, every square inch covered with startlingly bright frescoes from the 11th and 16th centuries. The yiayiá showed us the marble columns and slabs, scavenged from the pagan temple to decorate the interior. She pointed to small sections of the stone floor that have been removed to display pre-Christian mosaics.

Then she began a bitter lament over events that still choked her heart. How the Germans came and stabled their mules inside the church. How they allowed the manure and filth to pile up. How they built fires in the churchyard that blackened the interior and its precious frescoes. How, after the Germans left, the villagers gathered with shovels, brooms and mops to remove every trace of manure. To scrub away the soot and reconsecrate the space with their presence.

Today the icons are once again brilliant, the saints and sinners animate, seeming to breathe and nod in the flickering candlelight.

As we left the churchyard, we thanked the yiayiá and she give us her blessing. Then we regained the path and resumed our climb.

Pomegranates

Bill turned out to be a gifted wayfinder. He had the courtesy to consult me at every fork in the path, and I listened attentively and nodded every time. But the Meteora map he put in front of me may as well have been a map of Mumbai. Without Bill I would have been utterly lost in a second.

But there was a trade-off. I was the group’s only Greek-speaking member. So, while he took the lead on the paths, I stepped forward at every stop to chat, trade courtesies and translate. We climbed to the Monastery of the Holy Trinity, then to Varlaam Monastery. We poked our heads into dark caves, looking for bat shit (none), and hiked through damp, narrow passes where the sun never enters, and where temperatures plummet.

Hours later, we were back at the top of Kalambáka, surveying acres of clay-tiled roofs below.

Instead of taking a busy road back to our guest house, Bill suggested we take a longer route through the laneways that snake through the villages of Kastráki and Kalambáka. It was an inspired decision, as our route skirted fragrant backyards and gardens bright with bougainvillea and oleander, where cats dozed and small iron tables still held traces of that morning’s coffee. Giant red pomegranates, like decorative baubles, transformed every yard into an early Christmas scene. And so the narrow lanes we passed through had a holiday air, and in fact we were tired from our hike and these concluding moments felt like a celebration. As if we’d been soaring for hours high above, and could finally fold our wings and settle back to the ground, weary with exertion, our minds still giddy and crowded with saints and clouds of incense.

At an intersection where several backyards met, we paused to drink from our water bottles, and I watched as Bill reached across a fence to pluck a pomegranate from a tree. Seeing this, two other hikers walked over to another yard and picked their own pomegranates, quickly stuffing them into their knapsacks. I wandered on, pretending to look elsewhere.

But as we continued our descent into the town of Kalambáka, Bill turned to me and nodded at another backyard filled with ruby pomegranates: “C’mon, mate. It’s your turn now.”

Pears

Let me recount a story my normally laconic father told often, when he wanted to make a point. (He was more than laconic; he was actually born in Lakonia, as I was.)

It’s autumn and my father is marching on the Taigetus mountains with a band of irregulars. The Greek Civil War has erupted. Little-known outside of Greece, this vicious and partisan conflict will prolong the misery and slaughter of World War II, and will last from 1943 until 1949. It will rip families apart, pit brother against brother, left against right, republicans against monarchists. My father is on Taigetus to fight the Germans or, possibly, other Greeks. And yet, it’s a futile war. The spoils have already been divided, the end preordained. Greece will wind up on the western side of the Iron Curtain.

On this meaningless trudge through the mountains, the only trained and properly armed man is the commanding officer. The rest are ill-equipped and untrained kids. They’ve been issued antique weapons that may or may not fire, that may possibly blow up in their faces. They’re in street shoes and light jackets, slogging all night through the chill and wet of Taigetus, their fingers and ears numb with cold.

Exhausted and hungry, they’re now descending from the mountains and approaching a village. The early sun seems like a herald. Just ahead, they see an orchard of pear trees. Stomachs rumbling, a few drift toward the trees, when a voice rings out: “I will shoot the first one who touches a pear.”

It’s their commanding officer. His pistol is unholstered.

“They say we’re communists, thieves. That we don’t respect private property. I won’t give them the satisfaction. Now move on.”

I have no idea whether this story, filtered through an old man’s bitter self-regard and unreliable memory, is true. Maybe it doesn’t matter.

At dinner with our group in Kalambáka, where we spent three days, I led a small lesson in the proper pronunciation of the Greek name for Corfu, where we’ll be wrapping up our trip.

“Ker-ky-rá, Ker-ky-rá, Ker-ky-rá,” we chanted. The taverna chairs were accommodating, the night air was cool, and our table was laden with salads, stuffed vegetables, baked eggplant, saganaki, meatballs, baskets of bread and two half-litres of white wine.

But with talk of Kérkyra, I am getting ahead of myself. For we spent three days in Kalambáka, the large town at the foot of Meteora, where tourists arrive to lodge, eat and drink before making their ascent to the monasteries high above. Along the back streets of Kalambáka, every front yard had a pomegranate tree, heavy with ripe red fruit at this time of year. And in the agora stood crates of large yellow quince, also in season, beside boxes of chestnuts, tomatoes and squash.

Tourists come to Meteora to visit the ancient complex of monasteries, nunneries and now-uninhabited caves. Perched on improbably tall and inaccessible geological formations, the monasteries were built from the 11th to the 16th centuries. As for the caves, there’s evidence Neanderthals lived in them 50,000 years ago, later replaced by ascetics and hermits, shivering in the cold northern air.

There were originally two dozen monasteries, but only six are still occupied and tourists are allowed to visit only on certain days. Sometimes you’ll catch a glimpse of a monk peeking out from their private residence, dodging the tourists. You have to wonder about their restricted lives: While we’re gawking at the ancient icons, are they playing koumkán or watching Squid Game on Netflix? After so many centuries, why is this life necessary: To spread the holy word, to bolster Greece’s tourist economy, to pay for the monasteries’ upkeep?

From the heights of Agios Stéphanos, we watched enormous buses pull up, and out spilled the eager tourists, led by guides holding aloft a pennant on a stick. Since we’re so far north, it’s not just the usual cohort of Germans, French, Italians and Americans. Buses arrive directly from Bulgaria, Albania and Romania, just next door.

As we descend the steep stairs, the new arrivals struggle to ascend. “How much further?” they pant.

“Not far,” we say, conscious of the weight of our words. “Well worth it.”

The landscape of Meteora is otherworldly. You emerge from the darkened interiors, from the incense and icons and guttering yellow candles, and it all makes sense. Anything is possible here, so close to the clouds.

Kyría Kéti

Many years ago, out delivering groceries for my father’s store, I rang the bell of a ground-floor duplex. These were new customers, newly arrived from Greece, a certain Kyría Kéti and her husband. The woman who answered was nut-brown, barefoot, and wearing a white bikini. Twiggy haircut, dyed blonde. Frosted pink lipstick. Extravagant mascara. And, just below the Twiggy do, dangly earrings terminating in cubes of acid green. A Go-Go girl at least fifteen years out of date, but you could easily imagine Kyría Kéti, much thinner and younger, doing the frug in a cage suspended in an Athens disco. But here, frozen in time, she regarded me and my box of groceries and took a drag on her cigarette.

“Ah, yes, Kyría Afroditi’s son. Thank you so much for bringing my things,” she said, in musical Greek. “This way into the kitchen, please.”

I followed, and on the way glanced into her living room. A chaise-long, covered with a towel, had been set up in front of an open window. She had been sunbathing, and over the course of the next few years, whenever I drove down her street on a sunny day, I would glimpse Kyría Kéti reclining in her living room and absorbing the feeble heat.

As for her husband, I remember nothing about him. Except that he was unremarkable to the degree that she was not. And there was another remarkable thing about Kyría Kéti: her brother was a monk, and soon would be visiting from Greece.

A few weeks later, my mother summoned me to the store and introduced me to Father Nektário, the famous monk. Apparently, he’d been waiting some time for me to take him to Park Ex, as he only spoke Greek and didn’t know his way around. Could I do that, on the way to school? In the presence of a stranger, it was impossible to refuse.

I glared at my mother, and then froze. Was I was expected to kiss Father Nektário’s hand, as is customary? But this is a monk, not a priest, so do the same rules apply? Sensing my confusion, Father Nektário immediately seized and shook my hand.

The monk and I rode the bus, and afterwards the subway, and we talked all the way but I don’t remember a word. He was not a learned man, or at least he wore his learning lightly. Except that he radiated both quiet confidence and innocence. There was an unmistakable sense, too, of goodness — and I hesitate to use the word because it’s so vague and old-fashioned.

Like his sister, he, too, was a visitor from another realm.

Since I had to get to class early that day, I gave him instructions for when he got off at the Jean-Talon station: take bus 179 north; when it turns right on l’Acadie, get off at the stop after Ogilvy; turn right on Saint-Roch, and Tis Theotókou will be on your left. You can’t miss it.

He made notes with a pencil stub in a small book, and as we pulled into the Jean-Talon station, he thanked me. I considered kissing his hand. But, surrounded by strangers, I faltered and then my chance evaporated. He stood on the platform, a diminishing figure in black, and waved until he was out of sight. I never saw him again, for soon after he returned to Greece.

* * *

* * *

We emerge from the steep and rocky paths, between giant stone thumbs poking into the sky. Several rock climbers, bright dots on the dark-grey surface, are ascending one of the thumbs. After many hours of climbing to monasteries and caves, and then making a slow and uncertain descent, we’re now just above the clay-tiled roofs of the village of Kastráki, with the monasteries well behind us. Almost home.

We pause to admire a large handsome structure, cunningly built so it seems to emerge from Meteora’s strange geological formations. Workmen are completing the stone entrance, as a security officer smokes a cigarette and looks on. This might be a boutique hotel or a shipping magnate’s mountain retreat, we’re not sure. At that moment a crowd of people appears on the rocky path, led by a tour guide. We ask the guide about the structure but, surrounded by chattering people, and with the sound of hammering and power tools roaring in the background, I can’t hear a word.

Once we’re away from the crowds and noise, I ask one of my hiking companions to repeat what the guide said. “No one is allowed inside,” she explains. “This is where the last hermit of Meteora lives.”