After the celebration and a near-sleepless night, I stumbled into the kitchen and turned on the coffee machine, then the radio. A male voice came on. It said the Province of Alberta was in the grip of a weasels epidemic.

“The return of weasels is unprecedented,” a second voice said, sounding a note of panic. This one belonged to a doctor. “We thought weasels had been eradicated generations ago, and yet here we are again, having learned nothing.”

A baby had died, people were afraid to send their kids to school, many were signing petitions. And for some reason Mennonites were at the centre of this “entirely preventable outbreak of weasels.” Canada’s status as a developed nation may hang in the balance, one of the voices said, although I couldn’t tell which. No matter.

As the coffee did its thing, some of the fog lifted. I began to suspect an entirely different story.

I poured myself another coffee. Sat staring into the cup. Then gazed at a loaf of bread and tried to puzzle it out. What was that about weasels again? A long-ago album by Frank Zappa came to mind, Weasels Ripped my Flesh.

* * *

After too many beers and fried potatoes at a beach shack calling itself a restaurant, we’re careening along a back road in the Southern Peloponnese. Six of us, including my cousin and four of his friends, folded into a small, two-row Japanese pickup. Cigarette behind his ear, Stathi is behind the wheel. I’ve got one eye on the road as I strain toward an open window for a gulp of air. No one is saying much, we’re all feeling about the same. Every moment or two my head bumps the roof.

Ahead, the road is empty. Orange trees crowd us on both sides and the occasional greenhouse, a large ghostly white shape, sails by. During the day you can fry an egg on the blacktop, which is perpetually stained with streaks of green that indicate flattened lizards. But at night the sprinklers come on and the ditches fill with water and the air cools.

As Stathi steers into a gentle curve, the headlights pick out a pale figure standing uncertainly by the side of road, staring into the glare. The instant we pass him the guys in the pickup jerk their heads back. There’s a loud “Hey, pull over! That was Giannaki!” Stathi slams on the brakes and by the time we stop and everyone spills out, he’s trotting up.

I watch them surround Giannaki, slapping him on the back and rubbing his head. From what I can guess, they haven’t seen him for a while. He’s a strange fish, and in uniform. Wearing baggy green military fatigues, sleeves and cuffs rolled up high. Black army boots, unlaced, tongues hanging out. Except he has the size and build of a twelve-year-old boy. Sharp nosed, quick eyed, but with a strange confidence you don’t see in twelve-year-olds. I move closer and see a tattoo snake climbing his throat, whispering below his left ear.

In the way of semi-drunk male adolescents, there’s a lot of talk but no information. A lot of “Hey, how you been, you dirty dog” and “You know, same as you, bro’, just getting on, chasin’ the ladies” and “Getting’ your share of pussy, though, I bet.”

George introduces me as “My cousin from Canada.” Giannaki nods, doesn’t shift his gaze. I’m not sure he even hears.

When all the commotion finally subsides, Stathi says, “So where you headed, Giannaki?”

“Up the road and straight to hell, just like all you bad boys. Give me a cigarette and a lift and I’ll tell you when to stop.”

He hops into the back of the truck, army boots banging on the empty bed. I climb in after him, slowly. If I’m going to lose the beer, maybe it’ll be easier over the side of the pickup. Less messy, too. George and a couple of the guys also get in and Stathi drives off, taking it easy this time, with us in back.

Over the sound of the engine, the guys begin peppering Giannaki with questions. They’re curious but also wary. From what I can tell, his Greek is rudimentary, spiked with something I can’t quite place. I notice he keeps changing the subject but no one challenges him on it. “Are you kidding me?” he shouts in answer to every question. “Seriously?”

I can’t figure out if he really is, deep down, just a kid, with a kid’s astonishment at the still-new world. Or if he’s intentionally stopping the conversation dead. Ask a guy anything and what’s left to say after “Amazing!”? Amazing what, amazing how?

Eventually they give up and in the brief silence Giannaki turns to me and says, “So what’s your story, mate?”

The sudden English makes me sit up. That and the directness, the confidence. Like watching a precocious child actor take charge of a scene, hitting it on the first take. Then a light goes on: “Australian, right? You’re Australian!”

“Got that right, Sherlock.” He waits, as we continue to bump along the road.

“Oh, no story to tell,” I finally say. “Just visiting the old country. Seeing the cousins, making friends with their friends. Maybe drinking too much and picking up soldiers by the side of the road, too.” He doesn’t laugh. “What about you? What’s your story—mate?”

The other guys in the truck are watching, taking us in, even if they don’t understand a word. English is the stuff. It’s everything you want. Whiskey and leather jackets and Led Zeppelin and blondes in bikinis. Sometimes in the middle of the afternoon these guys and I will pass a bottle around until we’re drunk. Someone puts on Zeppelin or the Doors and they all look at me, waiting. Expecting me to break the code, pull back the curtain on the stuff. Head swimming, I try to translate, to give them what they want. If the lyrics are on the record sleeve, I’m in luck and I’ll take a stab at it. Otherwise what the hell is Jagger yowling about this time? Listening to “Purple Haze,” did Jimi just sing “’Scuse me while I kiss this guy?”

We pass a brightly lit house nestled among the oranges and for an instant I see a frayed sleeve, scuffed boots, no socks. I say, “Taking a few days leave, eh?”

Giannaki laughs. “Not exactly, mate.”

“What, then? AWOL?”

He giggles nervously, almost out of character. “Oh, we’re well past AWOL, miles past. But you know, comes a time when you gotta go. No need to panic just yet.” I don’t know what he’s talking about. He nods toward the orange trees. “I have a girl back there, so. Followed me from ‘Stralia. Straightened me out, I think. ‘Bout time, too.” Under the light of the stars and half-moon, pale hanging orbs stream by in the near-dark. “Just getting our shit together and in a few days we’re off.”

“Oh, yeah? Where to?”

Instead of answering he takes a long pull on his cigarette and studies the road. In the glow the sharp little-boy face is an old man’s. I notice a tiny scar on his chin, like something you get from falling off a bike. He looks at me for ages, says, “Don’t suppose you got any cash?” I glance over at the guys. They’re still watching carefully, still grinning and nodding their heads. This part of the Peloponnese doesn’t get many tourists.

“Still have some,” I say, touching the pocket of my jeans.

He says, “Just so we’re straight, I probably won’t pay it back. You might never see me again. Just to be straight, so.”

Later that night, after Gianniaki disappeared, after he walked away and I never saw him again, as promised, the boys gave me the backstory. How Giannaki had suddenly dropped into their lives. How his parents in Melbourne had packed him off to Greece before he killed himself with drugs or with the things you do to get drugs. How they’d managed to somehow get him into the Greek army…to, you know, straighten him out.

In the few weeks before he was expected to report for basic training, no one could keep up with him. Giannaki wandering the town at all hours, bottle in hand, howling in the night. Giannaki stealing a motorcycle and abandoning it in a nearby town. Giannaki discovered, next day, passed out under a café table in yet another town. Giannaki stealing his uncle’s hunting rifle and killing a neighbour’s dog. The uncle—rich, influential, persuasive—managed to keep it all quiet so the army wouldn’t get wind. And when the hour finally arrived, he, the uncle, personally delivered Giannaki to the assigned base and didn’t look back.

I dig into my jeans and hold out a wad of cash. It’s all I have left from the night. The guys in the truck are now looking away.

“Thanks,” he says, glancing up the road. He takes the cash, stuffs it into a shirt pocket, buttons the flap. Next moment he knocks on the roof of the cab and Stathi pulls over, cuts the engine. The sound of crickets surges up like a wall around our little scene. Giannaki jumps from the truck, crosses the road and turns around.

“God be with you, hooligans!” he calls in Greek, pointing at us. More than ever, he looks like a kid playing at something. We wave, say we’ll see him around, watch as he backs into a dark lane between the trees. Then he stops and takes a couple of steps back into the moonlight, as if something just occurred to him. “You never saw me, right?” He turns, vanishes into the night.

* * *

A couple of weeks ago, I picked up a book I hadn’t opened in years and out fell a business card. Waverly, Unusual Jewelers. The address was on Commercial Street, in Provincetown, at the tip of Cape Cod. Proprietor, Nick Quattrucci.

For several days after, I ransacked my memory. I’ve been to Provincetown five or six times, but the last time was decades ago. On which of those trips did I walk into Waverly, Unusual Jewelers? What caught my eye in the window and made me enter? Who is Nick Quattruci and why did I take his card? Nothing. The entire day, vanished without a trace.

I recently read that just about the entirety of our daily lived experience eventually slips away and into oblivion. Until something like a piece of paper falls from a book and causes you to peer into the darkness. As much as I tried, I could not resurrect Rick Quattrucci. But I do want to rescue Giannaki—”Little John”—while it is still possible. While parts of him survive.

Giannaki said I would never see him again. And now, with a bit of coaxing, he finally emerges from the darkness. A little worse for wear, barely recognizable. Now, small and pale and standing by the side of the road. Now, listing to one side, sewn together from found and discarded parts. Were both boots untied, or just one? Was there a scar on his chin? Who was driving that night? Did Giannaki even exist?

I guess as a small child fresh from reading “The Wind in the Willows” being immunised against Weasels would have appealed and I guess it did as I was. As to being a developed country perhaps you can develop too much country , at least that’s my feeling now ……………….thanks as always for taking us on a journey in words and pictures and provoking thought!

Andrew

LikeLike

Never read Wind in the Willows as a child, although I was aware of it. Which explains my alarm at all the weasels. As a prophylactic against the next infestation, I should pick up the book. Thanks for reading, thanks for taking the time to write a few words.

LikeLike

Gorgeous riff on memory and more. Thanks for the depths and the laugh past the halfway mark. And the challenge. It took a while, too long actually, embarrassing, but finally… weasels, what? No, um, weasels? Oh, right, … I won’t give it away, though maybe I’m the only laggard. Jane

LikeLike

Thank you, Jane. I did wonder if that bit would work, but what the hell. Thank you for reading and for taking a moment write something. Safe and wonderful travels to you and Sami.

LikeLike

Ahh yes weasels … it took me a minute or two. My first thought was of Poilievre, tbh.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In fact, an earlier draft extended the weasel thing and landed, predictably, on Poilever. I guess we’re both predictable. And you are…?

LikeLike

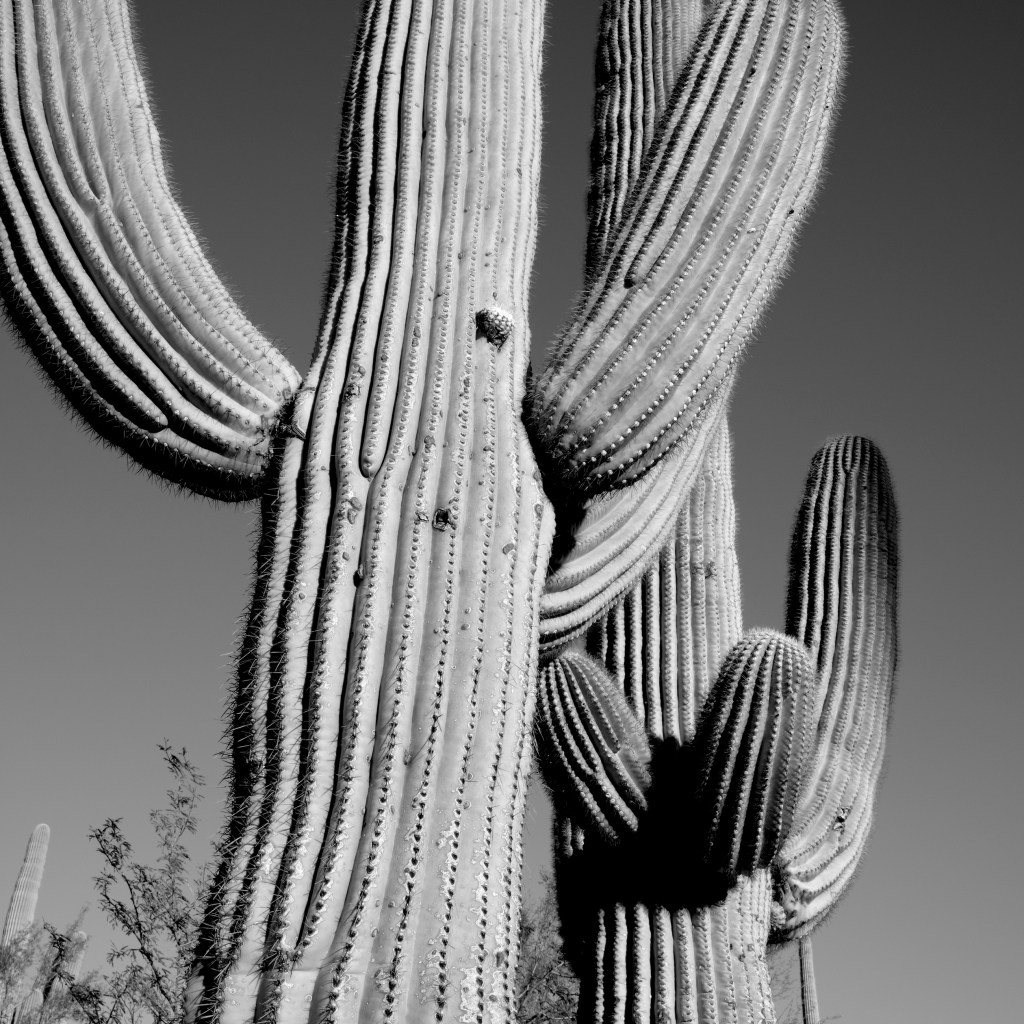

Oh what a treat to find this in my inbox. A wonderful story, as always. Thought-provoking and intriguing. The two photos that really caught my eye are the first and last of the collection at the end on the story. Bravo!

Alison (Hall)

LikeLike

Thanks for reading and especially for looking and responding.

LikeLike