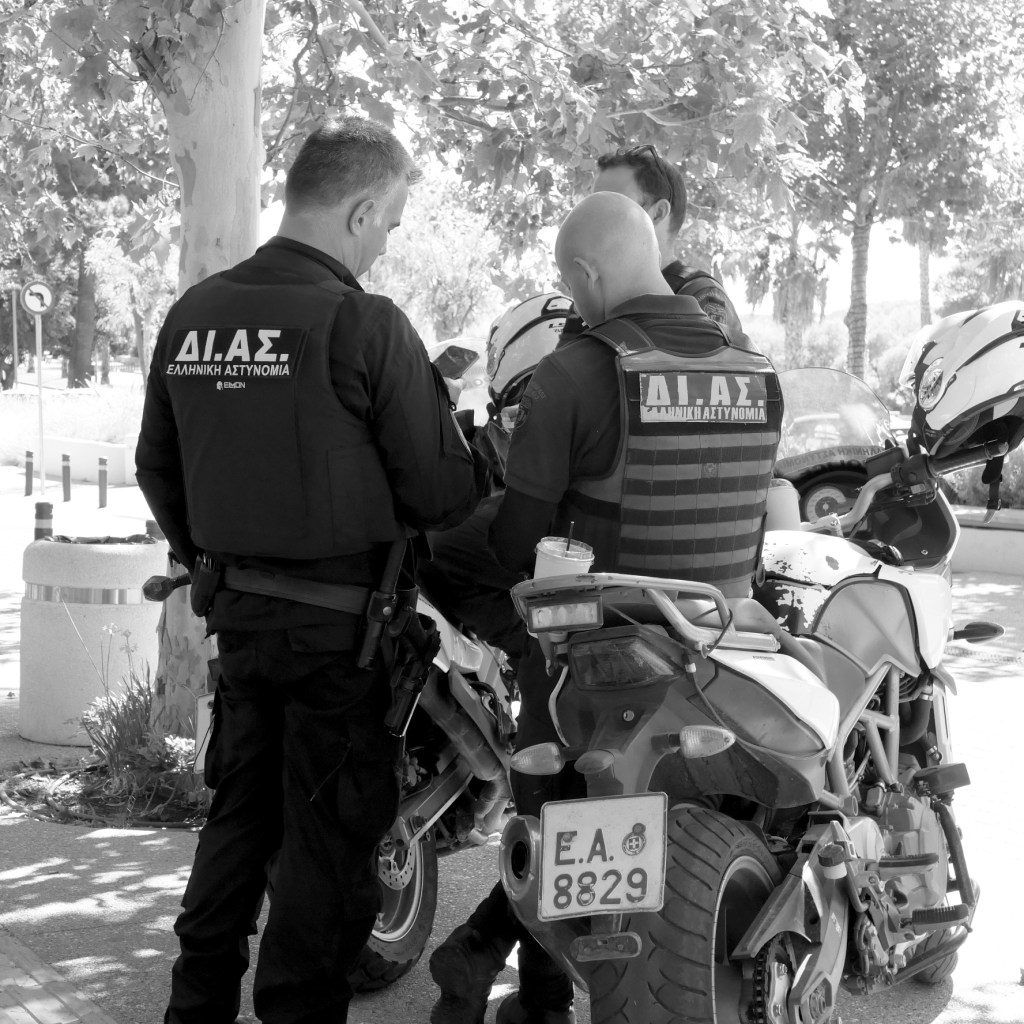

Greece is full of old things. Stick a shovel into the ground and chances are you’ll hit a stone phallus dedicated to the goddess Hernia. The ancient myths tell of how the god Meniscus mounted the sky-sent eagle Psychosis, which carried Meniscus high into lightning-laced clouds. From there, great and powerful Meniscus rained down his potent seed, and up from the sides of Mount Psoriasis sprang three divine sisters, Chlamydia, Nephritis and Diarrhea, handmaidens to mist-borne Hernia…

In Greece the past is everywhere, gumming things up. It’s one of the reasons the Acropolis Museum took so long to complete; same with the Athens subway. Just last May, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation cancelled a €4 million grant to build a cultural centre near Athens, after a mass grave from seventh-century B.C. was discovered at the site. This was the last straw. The project had begun in 2016, with superstar architect Renzo Piano at the helm.

* * *

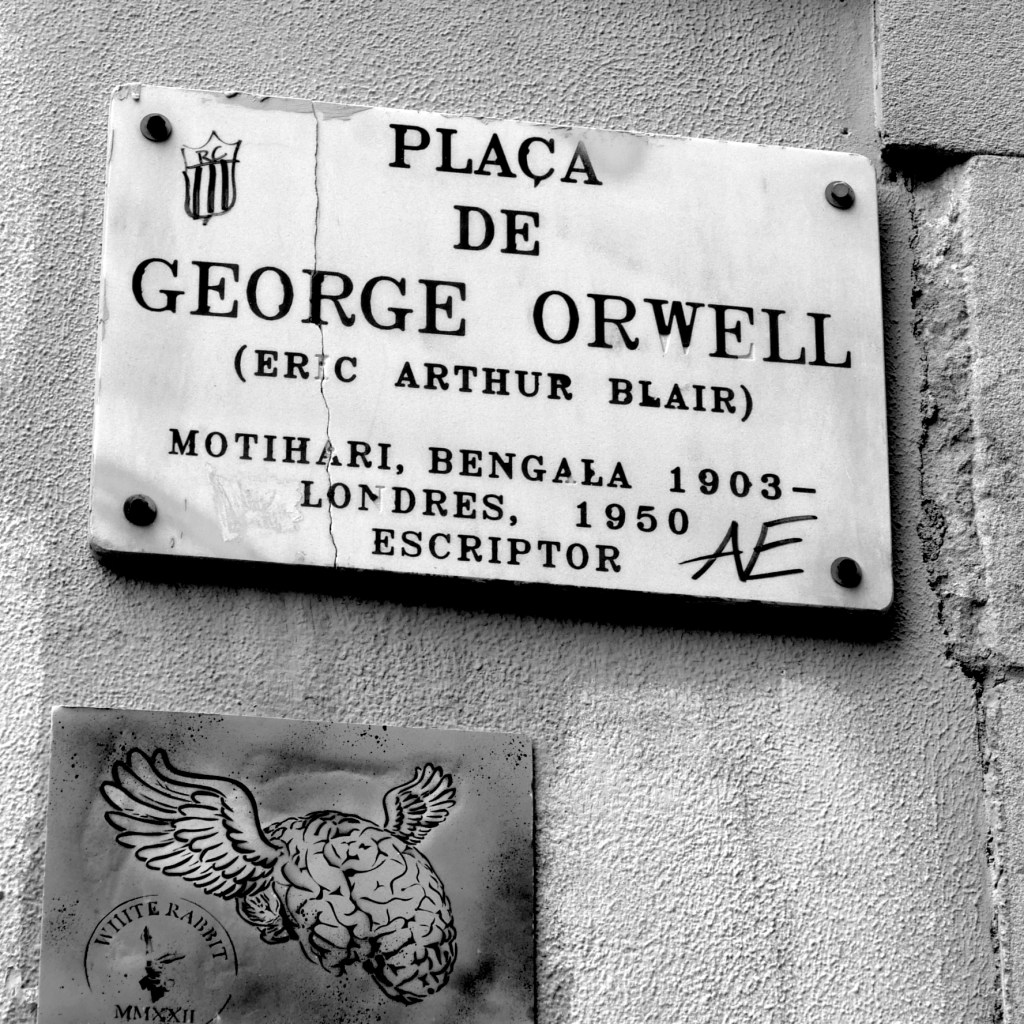

The ancients regarded Delphi as the centre of the world, and placed a bellybutton (literally, omphalós) at this spot. Western civilization was in its adolescence, a smiling self-absorbed youth, so you can understand the narcissism of thinking you’re at the centre of it all.

When you visit Delphi, you can view the omphalós, as well as the temple of Apollo and other structures built by successive waves of civilization, all of them eager to consult the Oracle. When she entered the right state of divine possession, the Delphic priestess could predict the future. So emissaries from many lands arrived with precious gifts to woo and consult her on their plans for battle and other weighty matters of state. Sometimes the oracle was right. And sometimes, maddeningly, she just wasn’t in the mood. So they’d wait and wait and sometimes lose patience and leave.

The museum at Delphi houses many fine statues, which will be familiar, if you’ve ever flipped through a textbook on the ancient world on a rainy afternoon when there’s nothing else to do. But that pretty much exhausts my interest in old rocks and Doric columns and such.

Manolí and his revíthia

I’m all for governments and academics digging up, delving into and protecting rocks until we know every damn thing about the ancient world. But do I have to buy a ticket?

I much prefer the living Delphi. That’s the town, a short walk up the road, that used to sit on the ruins but had to be moved so that French archaeologists, late in the nineteenth century, could dig and scrape to their heart’s content.

I much prefer Manolí, who brings me a chickpea (revíthia) salad, fresh bread and Greek coffee. The shops in Delphi sell ugly souvenirs, as they do everywhere in Greece. But the divinity of Greece is in its people, each of them interesting, interested and unfailingly polite. In Greek, any speech between strangers is formal — always with the vous — but richly laced with heartfelt courtesies and endearments accompanied by radiant smiles. What are rocks, after all, next to these beating hearts?

We’re sitting in a sidewalk taverna and an elderly Greek man with long grey hair, parted in the middle, is walking towards me. He wears a lilac shirt with a Betty Boop tie, above purple pants and yellow socks. In his hand, a chocolate ice cream, two scoops, on a waffle cone. Catching my eye, he winks.

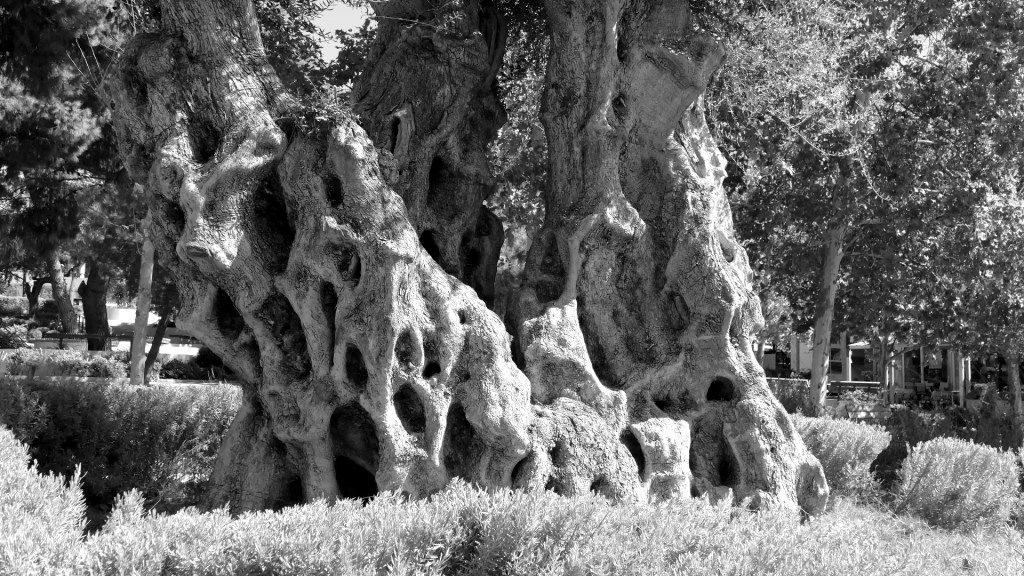

There are mysteries to be plumbed. Such as, where are the donkeys now? The mountain paths used to be choked with them. In the early hours of the morning, papou would load his donkey with a spade and pruners and baskets, with a small lunch of paximádi (hardtack), tomato, olives and cheese, maybe a hardboiled egg as well, everything tied up in a white cloth and placed in a plastic bowl. Then off he’d go to water and prune his olives and grapes. Dozing under a tree after his lunch, papou would allow the donkey to wander off, to munch on dry thistles and thorny scrub. And as the temperature rose and the crickets began their frenzied sawing, the donkey would commence his sorrowful braying song.