As I write this at an iron table in the South of France, a donkey is bawling his eyes out behind a stone wall. Meanwhile to my right and left, streams of churning water tumble and rush south on their way to the Mediterranean.

The sound of water surrounds us day and night. When it’s more than 30 degrees a short walk up the road, it’s nearly ten degrees cooler here. In this oasis, stands of bamboo, fig trees and cypresses everywhere, and everywhere massive plane trees whose infiltrating roots become witches’ hair in the fast-running streams.

We’re in the small town of Fontaine-de-Vaucluse, and I’m sitting beside the biggest spring in France, fifth-largest in the world. Its annual output, expressed in cubic metres of water, is a number that would bore anyone.

Better to imagine torrents of water gushing from beneath the mountains, branching into streams and pools of an unearthly green, in which ducks and river otters cavort. On their way south, several of these streams surround and flow beneath the Hôtel de Poète, where I sit at my iron table.

A short life of Petrarch

The poète in question is the 14th century Italian, Petrarch, who lived for a time in Fontaine-de-Vaucluse. You’ll find the Petrarch Column in the main square, as well as a Petrarch Museum and Petrarch’s Garden.

Now there was a productive life. Fiendishly prolific and active, Petrarch wrote hundreds of poems and dozens of books, served as an ambassador and poet laureate, was on back-slapping terms with Boccaccio and Pope Clement V. He was the first humanist and sparked the Italian Renaissance. He climbed Mount Ventoux, advised princes and wrote a famous sonnet to his beloved but unattainable Laura that students are still forced to memorize. At age 42, the sublime Petrarch was kicked by a donkey. From then on, he walked with a limp.

Speaking of donkeys, at dinner last night we learned that the donkey behind the wall is named Marcel.

Cavaillon melons in the rain

Market day at L’Ile-Sur-la-Sorgue, downstream from Fontaine-de-Vaucluse, and it’s pouring rain. Less than half the vendors showed up; most took a rain check. We order a PAC a l’eau at a café and wait it out under a stained awning. A few feet away, a bearded vendor with a giant sack of lavender is filling small sachets. Lavender scent soon fills the air. Once the rain eases up a bit, we buy a dozen sachets and begin to wander.

We behold great wheels of cheese, stacked loaves of snowy chèvre, braids of the purple-and-white local garlic. Cavaillon melons, prized across France for their intense flavour, are also local — the town of Cavaillon is just up the road. They are small, no bigger than a man’s fist. We first tasted Cavaillon melons in Lyon, and here they are again, in great overflowing bins.

But then the rain returns and we quickly retreat beneath a different awning, but with the same pattering sound.

Mad dogs and anglophones

The following day, at noon, when the mercury spikes into the high thirties, I elect to run along the Carpentras Canal. The canal is 69 kilometres long and descends from the high mountains, watering thousands of farms, vineyards and orchards across the region. In 1875, the bespectacled politician who led its construction was made chevalier de la Légion d’honneur by Napoleon III.

As I run beside the canal, magpies and blackbirds startle and burst from the tall grasses and wildflowers. After yesterday’s heavy rain, most of the poppies have vanished. But a few remain on the grassy banks: scarlet buttons on a green lady’s coat, sewn on with black thread.

I slow down for a spell to walk alongside a mayfly on a floating leaf. How slowly the canal water flows! At this pace, I might be walking beside an elderly aunt, bent at the waist, hands clasped behind her back, excavating the past.

* * *

The child would not eat and could not be roused from its bed. It remained silent. Its mother had consulted the old women in the village, and they had performed the necessary rites, but found no evidence of the evil eye. They prepared teas from various mountain herbs, summoned the priest to say a prayer, and still the child languished and would not leave its bed.

She waited until her husband was tending to some distant olive trees for a few days. Then, rising hours before daylight to avoid the heat, she placed a wooden saddle on the donkey, tied the child to the saddle and left for the town in the valley below. Arriving at mid-morning, she asked for directions and found the clinic, whose doctor had been born in her mountain village. When he saw the young woman, the doctor invited her in and called for refreshments, asked about village affairs, about the new priest. But then he noticed the silent child.

At the end of the examination, the doctor shook his head and said he could do nothing. God must soon take the child, and he gently suggested that she call for the priest again on her return.

The woman left the doctor’s office in tears. By this time the sun was high and the mountainside buzzing with crickets and heat. She took refuge by a stream beneath a plane tree and waited with the child for the afternoon. The donkey stood beside them, munching on dry thistles and grass. When the time came, she placed the child on the donkey and set off. She judged that there was enough daylight to ascend the most treacherous paths, and darkness would find them in familiar country.

Along the way her tears dried, as is common with people whose life is hard. The child remained silent and listless, but then it suddenly began to cry with new urgency. The woman took this for a good sign, a sign of the child’s struggle against death.

Her milk had long since dried out, but she had a half loaf of bread, a tomato and a handful of olives wrapped in a length of cotton and tied to the donkey’s pack. The child was too weak to eat, so the mother chewed these foods and placed the pulp between child’s lips. The child looked up in surprise at the tear-stained faced and swallowed. Along the way home, the woman stopped often to feed the child, the donkey waiting patiently all the while, the shadows lengthening.

God did not call the child on that day, or the next. The woman eventually saw her first-born grow into a man and serve in the war. He survived that too and settled into village life.

He played the fiddle at weddings, worked only when necessary and spent the little he earned on drink and tobacco. He was a tireless talker and sought-after drinking companion, a gifted mimic who charmed everyone in the agora.

The woman wept when her son left for Canada, and wept again when she read the letters announcing his marriage and the birth of his children. But the marriage was unhappy, and he soon settled into his old pleasures of song, drink and laughter. He lived to a great age, his children scattered, and when he died, he died poor and alone.

This life, my uncle’s life, did not have a triumphal shape or direction. Nothing can be learned from it. It does not make a story. Life came gushing from a mountain, formless and mysterious, to rush and stumble and vanish into the distant sea. The end.

* * *

Yesterday I ran too far along the aqueduct. I’m now feeling it in my joints. I’ll skip today’s run, maybe tomorrow’s too.

And so I’m back at my iron table in Fontaine-de-Vaucluse, beside the rushing waters. I have since discovered that the cavorting otters upstream from here are actually invasive North American muskrats. France has a muskrat problem. Ah, well.

The Saint-Véran church bell just rang the hour and, with the final peal still vibrating in the air, Marcel is at it again. I never can decide whether Marcel is laughing his head off or bawling his eyes out. Both make perfect sense.

Captivating short stories, Spyro. Love reading them!

LikeLike

Thank you. Glad someone is out there.

LikeLike

Always good to read your stuff😁 And the photographs!!!

LikeLike

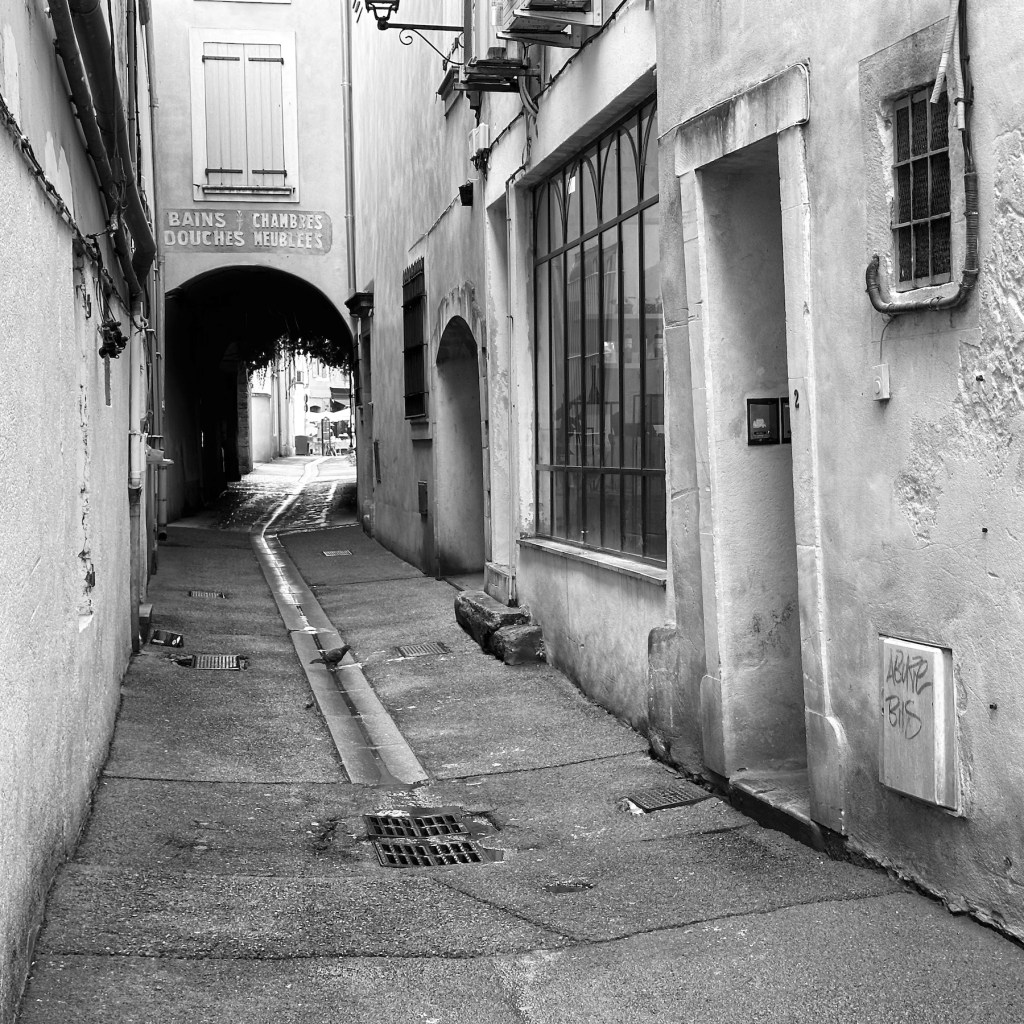

Ah, yes. The photographs, with no or only incidental connection to the words.

LikeLike

I’m out here too. Yes, captivating indeed. Wonderful pictures painted by words. And terrific photographs also, the canoes especially.

That take of your uncle, wow!

LikeLike

typo… sorry. “TALE” of your uncle.

welcome home by the way.

LikeLike

Thank you, Alison. Nice to be home, and to know that you’re reading and observing. Appreciate that.

LikeLike

ahhhh the loveliness of your words and the tempo of your writing is exquisite

LikeLike

Thanks so much: for reading and especially for responding.

LikeLike

thanks for the images of the scented land.

LikeLike

You have it right: in a place like this, sight and smell are the essential senses. So thank you.

LikeLike

Now I can’t stop wondering what shortcut I could dream up in the short time I have left to get on “back slapping terms with a Pope”. Thanks!

LikeLike

Forget it. You’re done, not enough time left. Thanks for reading.

LikeLike

Such beautiful writing…pictures…your uncle…love it all

LikeLike

Thank you, Mary. I’m happy that you’ve joined, you’re reading and you took the trouble to comment. Hope to see you soon.

LikeLike

I enjoy your writing so much! You take us on great adventures the way you weave everything together.

Thank you! Brenda

LikeLike

Thank you Brenda! Always good to read/hear your voice.

LikeLike

My garden is lovely and the sky is the kind of blue that promises endless summer, yet I’m restless in Lachine, so this story of southern France and somewhere long ago in Greece is entertaining, yes, but more than that, it’s necessary. Vicarious travel isn’t half bad.

LikeLike

I’m just happy you have the time and freedom of mind to read, and to come along with me. We will see you soon. I know it.

LikeLike